Time & Tide

I spent much of 1965 in Bordeaux - more accurately in the suburb of Le Bouscat. In January that year I had had an acceptance letter for university, and so I applied ...to become an "assistant d'anglais" for the remainder of that gap year. Although supposedly too late, I learned that the post in Le Bouscat had unexpectedly become vacant as the incumbent had gone home, and a few days later made the 24 hour journey by train and ferry from my parents' house near Huntingdon to the Gare St Jean.

And so it was that I started the first of 55 years working in international language education. I had been assigned to two schools, the Collège des Garçons and the Collège des Filles - the latter a particular challenge for an 18 year old apprentice in normality emerging from nine years of monastic boarding school - but it was an excellent way to get started. The staff were encouraging, and I was significantly helped in my work with the pupils by the fact of the astonishing success of English music. Often à propos of nothing they would say "Les Rollingstonne", "Les Beatles", "Sandie Shaw" or similar as I walked by; English had a role in their lives. In any case I was almost the same age as many of them and there were few barriers to communication. Meanwhile in Bordeaux the cinemas were showing, in addition to films with stars such as Alain Delon and Louis de Funès, a series of James Bond adventures, while British cars and even British fashion were gaining currency. It was not a bad time to be an English language teacher, 18 and in France.

And, oh bliss, my father had given me £50 to buy a Mobylette (d'occasion) enabling me to head into Bordeaux at the end of each day, to make friends in the restaurant universitaire, and talk and sing in the bar Le Plana on the Place de la Victoire (then a student bar, now a smart restaurant). Heading down the Cours de Verdun on my Mobylette one day I noticed a blue Cortina waiting to pull out into the road, and saw much to my surprise that it was driven by a school mate - Melvyn Master. Mel had been a year or two senior to me at school but we were members of the same house and as such more or less thrown together for much of our daily lives. In a largely grey world Mel had been an unforgettable and unmissable figure - physically imposing, a confident dresser, extrovert, quick-witted and entertaining. And, importantly, he played guitar and sang and wrote songs, and was a significant talent. We arranged to meet at a café nearby, and so the three of us - Mel, his wife Janie and I - began a new busking partnership. Mel, by now in the wine trade (where with his company Masterwines he is now as ever a force to be reckoned with) had married Janie soon after leaving school. Janey was an excellent singer, became a great friend and companion, and was - for those who can remember - a classy Mary to our Peter and Paul. It was fun, it worked well, we were good, and we enjoyed showing up unannounced and playing in the cafés of Bordeaux and of other places in the Sud-Ouest. And I recall a particular evening in Biarritz.

It started unpromisingly. We tried a large bar near the old port plage, but there were few people and no "ambiance", so we cut our losses, took out some food and wine that my companions had brought in their car, and then lit a fire on the beach where we restored our spirits as we ate and drank and ran through some of our repertoire. Our singing attracted a few passers-by, and before too long we had a small but appreciative audience. One among them came forward to say that he had a boîte nearby, and would we like to come and play there? We gathered our things and followed him by car through wooded sandy countryside to his crowded restaurant, where we ran through some pièces de résistance for an appreciative audience - Stewball, Manha de Carnaval, Blowing in the Wind. Our host then took an ice-bucket, generously primed with his own note for mille balles, around the assembled guests who responded in similar style. In good spirits we returned to the beach for more wine and celebration, and finally sleep; until we were woken by the beach sweeper's horn blaring the Marseillaise as we felt the first warmth of the bright Aquitaine sunshine, and watched the crashing waves on the rising Atlantic tide.

Danish Diversion

I was officially a "guest teacher" of English in the Copenhagen suburb of Hvidovre for the school year 1969-1970. Being a "guest" teacher was not quite the same as being a teacher, just as being a "guest" worker was different from ...being a local worker - in those days just about all "guest" workers (as the epithet was commonly understood) were from Turkey. "Guest" status gave me a certain freedom of action and once I had started bringing the guitar to whichever school I was working in - there were 7 in all - the pupils would ask for more. A local entrepreneur also booked me for school parties - all good clean fun.

It was a year's post and not renewable, but I wanted to stay in Denmark a bit longer and so I took a couple of teaching jobs in the city and supplemented my income a little by playing and singing - folk, calypso, ballads, rock, all sorts - in a bar called Det Lille Apotek. Today it is more obviously an upmarket restaurant - you could get food there in the old days but it was known and loved as a bar. (I should add that their website makes rather more of this and refers to Hans Christian Andersen as a regular for example, evidently a man who liked his sild og snaps). It got started after I was in there with a couple of friends one evening and pulled out my guitar and we started singing, and it went down very well with the management. They offered me an arrangement whereby I would be paid 85 Danish kroner in cash on any evening I showed, and it was entirely up to me to come or not. It wasn't a lot of money - although four evenings was enough to pay a month's rent - but it was useful and I probably would have done it for nothing as I had a lot of fun.

There were occasions when I was asked to sing traditional Danish songs - but I didn't know any. I could on occasion get away with offering my guitar for someone else to have a go, and the offer was sometimes taken up. I did however know the chorus to a Danish "Dansktoppen" hit of the time "Jeg vil saa gerne hjem til Fyn" as I had seen it performed in the Vise Vers Hus in Tivoli gardens by the songwriter himself, the mighty Thoeger Olesen, author of 2000 Danish songs. Played to a sort of Blue Grass / hillbilly rhythm which was faithfully reproduced by the Simonsen brothers (you have never heard Danish sound so Danish) who made the song a local hit, I remember above all that Thoeger clearly enjoyed singing and entertaining and that he got a terrific audience response with everybody joining in the chorus.

I did a fair amount of playing and singing over the years, but only once was I invited to give a performance for television. I never saw the broadcast and indeed I know nothing about it except that it was for a Japanese television company. A Dane in Det Lille Apotek asked me one day whether I would agree to play for Japanese television, and it was arranged for later that week. On that occasion, with a very bright light shining in my face, I sang Donovan's "Candy Man" for whoever it was, and for a couple of hundred extra kroner. The TV programme was of course about Copenhagen and featured Det Lille Apotek, where I was just lucky enough to be playing. If you find yourself in Copenhagen, try it!

Time & Tide

A few months after starting my teaching job in Tripoli in 1972, I was asked whether I would be interested in working in English language radio for, say, two or three evenings a week. I was quite excited about ...the idea of working in radio, and so soon afterwards found myself being interviewed in a curious little studio at the top of a building in a part of Tripoli that was otherwise dedicated to International Fairs. I was given the job, and for a period of about 18 months I would work there reading the news, making music programmes and talking to Ezzedin Serraj, the Palestinian who managed the unit. The news headlines were invariably concerned with what Gaddafi had said or done, typically followed by what Prime Minister Jalloud had done and so on through the upper echelons of the Revolutionary Command Council, before concerning themselves with the (unnamed) "Zionist entity", and other countries. I read this stuff without embarrassment mainly because I knew that almost nobody listened to it. It had no bearing on what locals listened to, no doubt much the same in Arabic, but ex-pats (and not a few Arabs) were tuned in to the BBC World Service.

Thus it was that I reacted with mild amusement only when asked by Ezzedin if I would record the translation into English of Gaddafi's "Third International Theory", since as far as I was concerned it just meant a little more time than usual in the recording studio which might otherwise have been spent in conversation. As for the international theory, however clear and intelligible the thoughts and words of the Colonel may have been, the translation was not helpful. At one stage during a recording session where I thought I knew what the author was trying to say, I went to ask Ezzedin whether I could change a sentence or two. "Change nothing" was the stern reply. So I carried on and eventually finished recording the cloudy ideas in broken English, having made the whole text sound as professional as I could.

It was several weeks later, shortly before we were due to leave Libya for a holiday prior to taking up a post in Kuwait, that I was reminded of the recording. The International Fair zone in Tripoli was hosting its annual international trade fair and we decided to take a look. They were selling tickets for access to the fair just next to the studio where I had spent so many evenings newsreading and making programmes, and on the building was a hand-painted map of the world. The Arab World was, as you would expect, covered in meticulous detail (no "Zionist entity" of course) and the rest of the world was more impressionistic. Well, actually it was slightly worse than impressionistic because there were no islands between France and Iceland; the British Isles had been spirited away. My wife and I were talking about this as we walked down an avenue of trade pavilions with tractors, diggers, printing machines and other industrial plant on view when suddenly I stopped to listen. Booming out of all the loudspeakers in the exhibition zone was my own voice uttering fluent but incoherent descriptions of true democracy, the role of people's committees and why that was superior to parties, representatives and voting. I was without doubt - until I explained what was happening to my wife - the only person who knew roughly what was being said, and who was saying it.

Even in those relatively early days of his rule, Gaddafi was known to be one brick short of a load. When the Libyan Arab Airlines plane was brought down by the Israelis over Sinai in 1973, and we all wondered what Gaddafi would do next, a well-connected Libyan we knew told us that Gaddafi had been placed under house arrest i.e. by his immediate team, who wanted to control over-reaction. In the event three days of relative silence passed, followed by an organised protest march in Tripoli.

A university colleague once told me that by reading the news in Libya I was a propaganda mouthpiece. That was a bit of a stretch, even a little bit flattering, since our listener numbers were very small, and the few we had were there for the music. I was just having fun, while Gaddafi was a psychopath.

Blacklist

During the period that I worked (moonlighting from my main teaching job at the university) in the radio station in Tripoli, I spent three evenings a week ...reading the news, preparing to read the news, and as a disk jockey making music programmes - one of which was named "Sounds of the 70s", copied from the BBC record programme with that title, and the other was "Records at Random", a name chosen by the station manager Ezzedin Serraj - and a name which fairly reflected how things worked at the time. I enjoyed working with Ezzedin. He was a short, round Palestinian, a good listener and talker, and during those evenings at the station - where I would typically be on duty for a little over three hours - there were numerous occasions when little was happening and we were able to discuss current affairs and such. Ezzedin was a paradox, being on the one hand something of an Anglophile, and on the other an early refugee from his homeland following the formation of the nation state of Israel when he was a young man (he was now about 50 and this was the period 1973-1974). He forgave the British much, but not what he saw as a critical decision by the British to hand over their arsenal of weapons to the Zionists.

Our conversations were however not always so earnest. One evening Ezzedin asked me if I could procure a bottle of "Flash" or "White Lightning" as it was known locally - illegal hooch which was made by ex-pats; Libya was "dry" and there was no legal alcohol available. The reason he gave was that he had "a romantic appointment" with an Egyptian lady and he thought that a drink might help them to get along. I didn't use the stuff myself, preferring instead to brew my own beer at home - malt could be obtained easily from a local pharmacist ("for the children?" he would ask with a knowing look) - but it was not difficult to obtain the hooch, and I knew a chap called Len who made such deliveries on his moped, and I bought a bottle from him. This I smuggled into the radio station and Ezzedin hid it behind his desk. At our next meeting he declared himself well satisfied with the purchase; "she was like a tiger", he said.

What was being broadcast at any given moment was monitored by the simple expedient of a small transistor radio, tuned to the radio station, which sat on Ezzedin's desk, and when we talked he sometimes turned it down very low, or even off. Thus it was that we were talking one evening when one of the station technicians, a Libyan called Ali, burst into the room shouting "Je t'aime". A declaration of love from Ali was improbable, and we knew immediately that the reason for the drama could only be that, at this stage for reasons unknown, the station was broadcasting a blacklisted record - the risqué / explicit hit by Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg "Je t'aime - moi non plus". Anxiously Ezzedin turned up the volume on his transistor radio only to have his worst fears confirmed. The team scrambled to change the tape, and the immediate crisis was over.

There was another outsider like myself, an American we shall call Ryan, who for a couple of months also made some music programmes, and he had deliberately dropped this song in to create maximum disruption. This was - in Libyan terms - a serious offence and, as the responsible manager and obvious scapegoat, Ezzedin was clearly very upset about it. The list of blacklisted songs and artists was long; once a singer had performed in Israel - e.g. Barbra Streisand or Frank Sinatra - he/she usually was added to the list, but individual songs such as "Je t'aime" could be put on the list with no requirement for a committee decision. The list included, for example, "Love Train" by the O'Jays and when I asked about that I was told the song included a reference to Israel - a country which was still officially referred to in Libya as "the Zionist entity" (as required by the Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council, Colonel Muammar Gaddafi) and, since it was a turn of phrase that hardly tripped off the tongue, the O'Jays were unlikely to have entertained it. It seems that Ryan made one last programme before leaving Libya to return to the USA, and that is when he set the trap. By the time it was broadcast he was far away.

The good news was that no Libyan official of any consequence (or otherwise) was listening, and no action was taken against the station or Ezzedin, who lived to fight - and hunt the odd tiger - another day.

Wheels within wheels

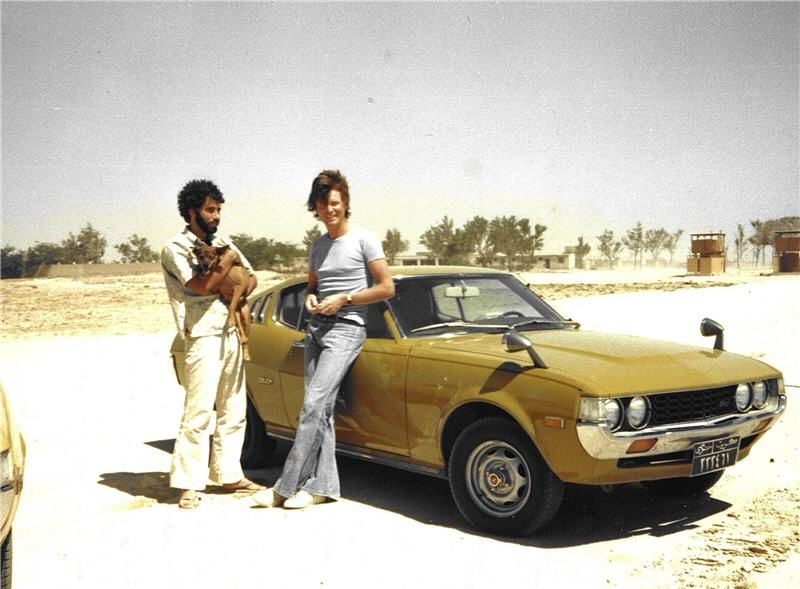

In 1976 I became the proud owner of a new Toyota Celica "Liftback", sold by Al-Sayer in Kuwait. It had air-conditioning, a cassette player for my Areth...a Franklin, James Taylor, Stevie Wonder tapes, alloy wheels - pretty cool I thought. I used it to drive to work at the university, to go shopping and so on, and once or twice a week for the stretch down to Al-Ahmadi where I regularly played cricket for the Kuwait Casuals. I enjoyed the driving around Kuwait despite the traffic jams and the "creative" driving, because the Toyota A/C worked well and kept the inside of the car cool, while the music was excellent and I enjoyed every beat. Like a lot of buildings in Kuwait in those days, the block we lived in Al-Khaled compound on Baghdad Street had space under the building for residents' cars, and this was not only very convenient but significantly, as anybody will tell you who has lived in those parts, it was a type of construction that kept the car out of the sun.

My peacock pride in my cool-image car took a hit after only two weeks. I came down after breakfast one morning to go to work to find that all four wheels had been stolen. They had been replaced with a set of old, battered wheels, the tyres of which had been cut and destroyed. The good news was the car was off the ground, but the bubble had burst and the car was motionless. I contacted my insurers who advised that I would need a police report, and a friend drove me to the police station where I regaled a somewhat reluctant official with my story. He had to be taken to see the car for himself, and eventually gave me the document I required. Or at least I thought he had - in fact the police reported that only two of my wheels had been stolen. However the insurer obligingly accepted my version of events and gave me cover to get four replacement wheels from Al-Sayer in Shuweikh. They had only two in stock. They were the wrong colour - black - but were the right specification. The Al-Sayer employee then very kindly took a spare wheel out of a show car and gave that to me so, with three new wheels from the official agent and the spare wheel which the thief had left behind, I now had what I needed in order to be mobile again. Not so cool, but mobile. Although I assumed that would be that, the story does not end there.

A few weeks later I crossed Baghdad Street to the general store where we sometimes bought provisions. Outside the shop, parked on the sand, was an old and battered yellow Toyota Celica with new alloy wheels. No, this was not a coincidence; I knew these wheels were unobtainable in Kuwait and they had to be mine. The driver when he appeared could not have looked much shiftier or more guilty. I said "sayerra gadeem, iulaat judud", the car is old the wheels are new, which provoked an outburst including repeated protestations that he had bought everything from Badr Al-Mulla. He got into his car and drove off. I rushed back to my car and quickly caught up with him and stayed on his tail - not a "Bullitt" style chase as I just stayed in his mirrors until he stopped again. We both got out and I went to talk to him a second time when I got the same story although his defeated manner made it clear that he could see the game was up. In fact he was in more trouble than both of us knew. By chance I had been at school in England with the boss of Badr al-Mulla, indeed Anwar and I had even played in the same Under 11 football team. I took the registration number of the old car to Badr Al-Mulla and Anwar's Indian clerk quickly discovered from company records that the car was sold to an employee of the company. Leave it to me, said Anwar.

Two days later I was invited back to the company HQ where Anwar invited me to pick up my wheels, and showed me the now redundant employee's yellow Toyota beached nearby. Having thanked my fellow footballer for his role, I was assisted by his clerk as I loaded the wheels in to my car. "I told him", said the Indian pointing to the now scrapped old Celica, "that he made a big mistake to steal wheels from a friend of Mr Anwar". You can say that again.

Programme R&D (1)

After the 1973 war and the oil price hike, money poured into Kuwait, not just wealth, but a flood of money. We saw, for example, the roads around Kuwait City being embellished with ...new street lamps and, soon afterwards saw those new ones being taken down and replaced with other even more splendid lamps. Everything was expanding at a rate of knots and the levels of investment were eye-watering. One can only imagine how all this money was influencing the corridors of power, but from where we sat as teachers at the university the Kuwaitis seemed to be managing it all well enough. Government salaries rose a bit faster than prices so we were mainly content. But not everything could, of course keep up and most obviously up and down the Gulf - and across the whole Arab world - there was a dire shortage of hotel rooms, as planeloads of delegations arrived to sell their goods and services.

In early 1975 I was the beneficiary - I think that's the word - of some university wrangling. Quite early on in my time in Kuwait I had heard about the likely expansion of the Language Centre, imminently to include the forthcoming College of Engineering , and I made as much of a point as I could that I had taught engineering students in Libya. And as luck would have it one of my colleagues, American, was married to the Kuwaiti who had been appointed as Dean of the new college. She passed on news of my credentials, and I was duly given the task of setting up the English Language Unit there. To begin with the College consisted of the Dean, his immediate office staff, and myself - no academic staff and no students, and happily the dean, Dr Riyadh, and I got on well. I was able to plan the programme and was subsequently given the pick of the newly recruited teachers. Meanwhile the head of the Language Centre, a Palestinian, had arranged a tour of Egypt, Jordan and Lebanon in order to research how the expansion into other faculties might take place. Exactly what happened I know not, but the Language Centre director was not a popular man, and quite unexpectedly I was asked by my new dean to undertake such a tour myself, effectively taking the other man's place. The money had been budgeted, all I had to do was to agree to go, and I had no difficulty with that. My only requirement was that I should be able to choose where to go. I knew of the ESP work being done by John Swales and his team in Khartoum, and by Tony Dudley-Evans and his team in Tabriz, and of study skills work being done at the American University of Beirut, and so I drafted an ambitious whistle-stop tour which eventually became Kuwait, Cairo, Khartoum, Beirut, Tehran, Tabriz, Tehran and back to Kuwait in 8 days. I got my ticket OK, but hotels?

After a delayed flight from Cairo and then taxiing round Khartoum in the wee hours I was eventually admitted to a sort of multi-bed dormitory in a house with no glass in the windows, where such security as existed was a function of a guard sleeping across the door. The door itself had no glass in the windows either so his existence was as precarious as any. After a short and sleepless night I headed for the university of Khartoum where I met John Swales who generously invited me to his house where he and his wife Val kindly saw to it that I was fed, watered and rested. And so, before leaving, I was able to conduct a little research, collect materials samples, talk about syllabuses, and discuss ideas for implementation. Plus visit the "Sudan Club" and see the confluence of the Niles.

Thence to Beirut for two nights where I got a room, and was able to pay an extended visit to AUB (The American University of Beirut) and learn about their (at that time) leading edge study skills programme. Next day I headed for the airport to get my Swissair [sic] flight to Tehran. It was April 12th 1975, and the airport was packed out. There was a lot of tension in Beirut at the time and people were evidently keen to get out, and I was shocked to learn that my ticket was no guarantee of a seat on my booked flight; many more had been booked than could get seats on mine and other flights. Hundreds of us were corralled into an area where periodically an airline official would stand on top of a chair and shout a name or an instruction in Arabic. And there I had a stroke of luck. An official said in English there was one more seat that could be taken by a passenger travelling alone. I raised my hand, shouted and jumped up and down to attract his attention and he saw me and shouted "Bassbor!". I pulled out my passport and threw it about 25 feet over the heads of the crowd in front to where the official was. He checked it, nodded and beckoned me over so that the crowd made room for me. Thus I got out of Beirut, headed for Tehran. The next day the tensions between the Phalangists and the Palestinians exploded, and the civil war that was to blight the country for the next 15 years made its bloody start.

Programme R&D (2)

Having collected my suitcase at Tehran I cast about for a taxi, and when a man said "Taxi?" I said yes and was taken to a car park and put into the car and asked to wait. A little later ...my driver returned with an Italian businessman. We were a little surprised to find we were sharing, but things were typically not well ordered in those days so we just accepted that he was probably not a licensed taxi driver but as long as we got into Tehran and found a hotel... In fact we were only a mile or so from the airport when we were pulled over by the police and all of us taken to a police station. The driver was indeed unlicensed, so we were all breaking the law. In the end the Italian and I were cautioned and allowed to leave. By this time my travelling companion had learned to his surprise that I had no hotel room. He kindly offered to let me park my suitcase at his company offices, and we arranged that I would meet him there at around 6pm when he hoped that his company would have found somewhere for me to stay. My visits that day included Arya Mehr University of Technology where I met an American in the English language department and we talked about ELT. I was at that time committed to the concept of ESP - English for Special Purposes, the tailoring of an English course to meet the needs of science/technology etc students - and here was a man who clearly thought it was bunk. There was English, and you either learned it or you didn't. He showed me some US-published ESL materials which rightly or wrongly I could not imagine using - and which I am sure would have been banned a few years later when the Shah was deposed and the Ayatollahs took over (and the university, with the Shah no longer the "Light of the Aryans", changed its name). I found the building where I had left my suitcase and made my way to the office which was now closed. With no choice, I sat on the staircase of the deserted building outside the office for an hour, and had begun quite seriously to consider the possibility of sleeping there when to my intense relief I heard Italian voices coming up the stairs. The slightly less good news was that they had not found a hotel room, but my travelling companion had a big room and there would be room for me there. So, both, ahem, straight, married men we shared thanks to his generosity and "the kindness of strangers". I had, by now, learned a lesson, and since I was due to spend one more night in Tehran after my trip to Tabriz, I managed to get the hotel's assurance that I had a room booked for me for the night of the following day.

In Tabriz there was no hotel room. I met Tony Dudley-Evans there who was head of the ESP project, and he very kindly offered me a bed, so that was OK. The work in Tabriz was of interest, and it was that which produced the "Nucleus" series of books published by Longman, which was perhaps the biggest ESP splash of the age. At the end of the day I flew back to Tehran and went back to my hotel, confident that a room was waiting for me. It wasn't. The different receptionist had no idea what I was talking about, no there were no rooms and the hotel was full. With nothing to lose I insisted and explained that I had stayed there two nights previously and gave him the room number. He looked it up and said that my claim was impossible ; that room was occupied by an American family who had been there for a week. But that was impossible as I knew. Eventually - and I ask the reader to bear in mind that in 1975 only the grander hotels had a computer system worthy of the name - we walked to the room together and he used his master key to open the door. And there was an unused, made-up room which the hotel receptionist then told me I was free to use. Piece of cake.

Gate of the Winds

In the summer of 1978, after four years working in Kuwait, Bente and I returned to England by car. Obviously this was not a spur of the moment decision..., and there were many chores to complete in advance of the trip: the car insurance, the maps, the visas for Saudi, Jordan, Syria and Turkey, the planned stops, crossings and so on. There was of course no "online" in those days, no Google maps, and indeed not only no mobile phones, but no phones at all. We had a phone in our flat in Kuwait because I had a student with "waasta", influence, who arranged it for me, but my colleagues were mainly not so lucky so not much use was made of it, and it was really just a sort of status symbol, generating admiration and curiosity from visitors. We didn't miss what we didn't know and knew that we would have to depend on our wits, hospitality and good will. We were fortunate to know someone who had made the overland journey a year or two earlier, and his experience and advice saved us at least one major problem, namely this: we were advised to tell the Syrians on entry that this was a holiday trip and that we were returning to Kuwait, for otherwise they would seize the car as commercial goods and require us to head for a ministry in Damascus to get permission and pay duty. It was not the only lie we told.

Having spent a night (our second - the first was at a small hotel by the Roman Theatre in Amman after completing the extended 1000 mile drive from Kuwait) at the rather splendid Baron Hotel in Aleppo, we headed for Turkey. It was to be a few years later when working in publishing for Thomas Nelson that I saw the trulli - the sort of beehive houses of Puglia - but it was on this day in Syria that we saw them for the first time as we drove through the heat towards Bab el-Hawa - the "Gate of the Winds" - eventually reaching the Syrian border where I parked the car and took my passport and sundry papers into the border station where I was directed into an office where there were two uniformed officials in conversation. There was no greeting here, just one word "bassbor". I handed over our passports to the official who simply opened the drawer of his desk, tossed them in and slammed the drawer shut, and then carried on talking to his colleague. I should say that I had by this time lived in the Middle East for six years and had had more than one what you might call "cultural experiences", so I did nothing and simply stood by the desk. After a few minutes the same official looked up at me and said "Shinu tibi?" - what do you want? I told him I wanted my passports back to which he replied that they were no good. He asked me what currency I had, and I said I had very little. "Inta muhandis?" he asked - are you an engineer? "La'", I replied negatively, "ana mudarres" - I'm a teacher. It was not the first time that I was made aware of my lowly status. His face fell, he asked for the equivalent of about five pounds which I gave him, stamped the passports impatiently and, after a quick inspection of the car and asking who the woman inside was, he allowed us to go. There was then a fairly extended drive through the mountainous no-man's land to the Turkish border. The guard there was, if possible, even less interested in our passports and for the second time that day I was asked what currency I had. I told him I had none because I had given it all to the Syrians, and volunteered this time that I was a teacher. Neither point was challenged and, in good order but for the marginal damage to my virtue, we headed for Adana.

One to Ten

I don't know what it's like today, but 40 or so years ago parts of rural Turkey were pretty wild. We drove along narrow mountain passes with nothing between us and a precipitous... drop, roads where the occasional oncoming truck appeared to demonstrate complete indifference to our potential fate. We treated this traffic with respect, stopping as near to the edge as we could to allow them to pass. We also took extra care driving through villages where the children seemed to treat us with much the same nonchalance as the trucks, and so to put themselves in danger. And therefore us too; we had been advised in Kuwait that in the event that the car was - heaven forfend - in an accident involving a child, the best thing was not to stop but to drive straight to a police station and hand yourself in. Getting out of the car to help could be fatal as a member of the child's family might well seek revenge. Fortunately no such thing threatened to happen.

Our first night in Turkey, the third of our journey, was spent in Adana. We found a satisfactory hotel, and that evening had a simple if hygienically challenging meal in a local restaurant. People were courteous and friendly, the temperature was balmy, the town was animated and we enjoyed the atmosphere and watching the people of Adana going about their business. We were also excited about our trip, and looking forward to the following day when we were headed for Cappadocia. It was a Turkish colleague in Kuwait who had told us that it should not be missed, it was a minor detour and we were keen to see what was there. It was, as anyone who has been there will know, extraordinary, unforgettable - above and below ground. It was here, in Göreme, that after four days of intensive driving we broke our journey for the first time and spent three nights in a little hotel which we used as a base to explore the area. I suppose that even in 1978 there must have been package tours to the area, but we saw no evidence of this and it felt as though we had the place almost to ourselves. We saw no balloons, no crowds, no chain hotels. But we did see the underground churches, the troglodyte caves - some clearly still inhabited - and the extraordinary, puzzling and precarious rock formations.

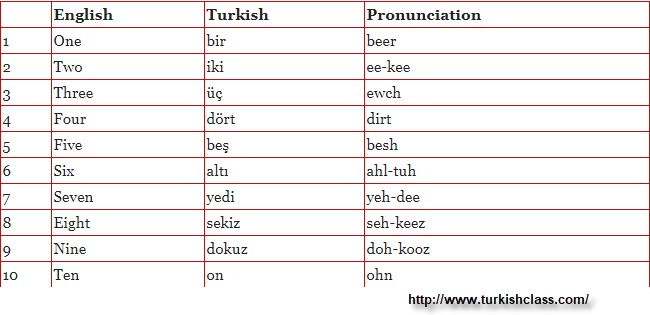

But it is an incident on the journey to Cappadocia that I now relate. We stopped for lunch about three hours out of Adana having taken a very minor road to a spot where we would be alone and with a beautiful view. Quite soon we heard some voices and a group of five or six children appeared from - it seemed - nowhere. Their leader had a catapult which he appeared ready to use and as aliens we were, it seemed to me, potential targets as they stood about 30 yards away and shouted at us. I have no idea what they said, but the tone was mocking rather than friendly. I walked towards them beckoning, inviting them, smiling and using eating gestures. So they decided to investigate and came to join us. We didn't have much extra food, but they had some of our bread and were clearly appreciative. We had, however, not a word in common - they no English, we no Turkish. So I started counting, and using my fingers, one, two, three. And asked them to do the same. A few minutes later they were counting to ten in English, and enjoying my efforts to do the same in Turkish - and indeed we got there - one to three, then one to five, then six to ten and eventually all fingers on both hands were accounted for in both languages. Honour was satisfied, it was a happy encounter, we said a friendly goodbye and moved on.

A lucky break

After teaching abroad for several years, and following our epic car trip home from Kuwait, I took up a post as commissioning editor with the ELT Publishers... Thomas Nelson in Walton-on-Thames. After working as a teacher in France, UK, Denmark, Libya and Kuwait, and with a PGCE from UCNW Bangor, I could say I knew something about language teaching, but I really knew very little about publishing. My excellent boss Van Milne was not really into formal training courses and preferred the idea of picking things up and learning on the job, and I found, particularly in the early days of production meetings, that there was a lot to understand. I had some junior colleagues with years of experience and I was surely a source of frustration to them, but we all had to bash on. My job was to identify markets, projects and authors and in this way to bring new marketable ideas, manuscripts and ultimately books into the company. It was in many ways a plum job.

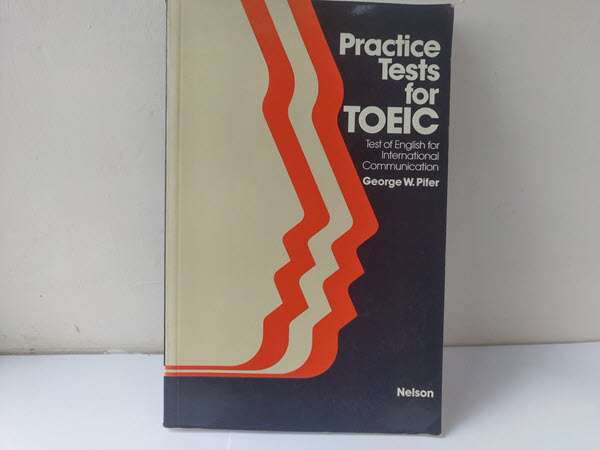

My first overseas assignment in the spring of 1979 was to attend a conference in Ottawa and take a view of opportunities in Canada, and - to cut a long story short - my conclusion was that Thomas Nelson of Walton-on-Thames did not have ELT publishing opportunities in Canada. My recommendation was therefore to draw the line there. It wasn't a way of making myself popular but I had (and have) no regrets. My second overseas assignment - to go to Japan in late 1979 - changed everything. The company had no suitable product for that market, the Japanese were not interested in Cambridge exams, it was more of an American English than a British English market, but above all it needed special attention. Japan, as everyone who has been there knows, is different. I attended the JALT Conference in Kyoto, and after that headed for Tokyo to see what I could find. A very helpful Mrs Nishida at the British Council set up some appointments for me, which included a visit to the personnel department at Nippon Steel Corporation, at that time a company with 12,000 employees. By happy chance I asked the right question, which was "How do you assess the English language ability of your staff?" They used, they told me, the "STEP Test" (an answer I had heard already several times elsewhere), but they now planned to use TOEIC. What? I had never heard of it. TOEIC was in fact entirely new and indeed the very first sitting of the test with 3000 candidates took place in Tokyo that same week in November 1979.

In the next few days, while still in Tokyo, I visited the offices of the company managing the local marketing and administration of the test where I met the general manager Ito-san, made contact with ETS Princeton and Dr Protase Woodford who managed their end of the project, and while still "flying blind" but with the full support of those two key players, commissioned an American Newbury House author George W. Pifer, then working at the Japanese American Conversation Institute, to write what was to be the very first TOEIC publication for English learners: "Practice Tests for TOEIC" - as in the picture above.

There remained a thornier task - to garner the support of my marketing colleagues at Nelson on my return to Walton. They had, of course, never heard of TOEIC, did not know much about Japan, and were not keen to support something so unproven (especially from an editor who had not earned his spurs). I managed to get enough support for them to pursue their enquiries themselves on the next regional sales trip, but here too we ran into a problem. The company in Tokyo had told me that they were already planning expansion into South Korea, and that a major company there - "Sansei" - was taking the lead, and I passed this snippet on to my marketing colleagues. Unfortunately the manager in question returned from Korea saying nobody had heard of this company.

I managed to get the project started and when I went to Japan for the second time, the project was in pre-production and nearly, but not quite, a book. I called at the International Communication company offices again and mentioned to Ito-san the failure by the company's marketing manager to identify the Sansei company in Korea; this was greeted with utter disbelief - it was, he said, one of the biggest companies in the world! And so it was that I learned that "San sei" is how the company is known in Japan, being Japanese for "three stars", and that three stars in Korean is "Sam sung". Doh! Forty years on TOEIC is taken by millions and there are books galore directed at the market, including several more by George Pifer. And the leading markets for the test are Japan and Korea.

Chance Encounter

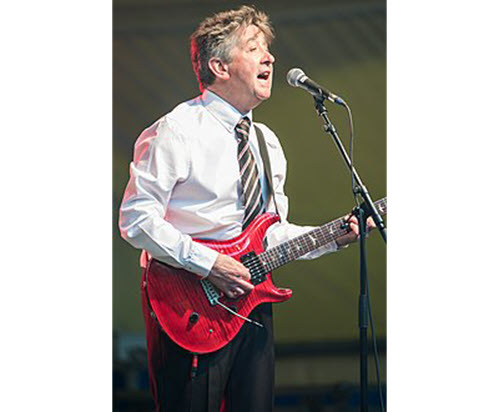

By 1968 I had had a fair bit of experience in singing and playing guitar to different audiences having done some busking in France and playing in a band in Cambridge. During the summer of that year, at a country house gig, ...I met somebody with showbiz connections who asked me contact him at his office in Park Street, central London. It was, as it turned out, an extended red herring moment and I will not cover every twist and turn of the story here. Except perhaps to say that the episode came to an end when at an audition in the EMI studios in Abbey Road I sang an original song written by a friend of a friend when I really should have sung something I both liked and knew better. No matter. One stop along the way to Abbey Road was an audition in the private flat of Tony Hicks, the lead guitarist of The Hollies, where also present was a certain Phil Solomon who, I was informed, was manager of The Bachelors, the Irish band that enjoyed considerable success in the 1960s. That bit went fine, and Tony Hicks suggested some songs for me, and the subsequent abortive studio audition was arranged as a result. Anyway, that was then, and later that summer, driven by a need to earn a living, I got a job as a French teacher in Surrey and, while music and guitar remained an important part of my life, by the autumn of that year I had given up any idea of entertaining professionally.

Over the ensuing years I taught French in England, English in Denmark, got married and went back to university and then taught in Libya and Kuwait before starting a new career in ELT publishing. And so it was that, while travelling for my company in the early 1980s I happened to be in Bahrain where quite by chance I bumped into a former colleague from Libya, one Jimmy Turner. Jimmy told me that it was, that very day, his 40th birthday and he was having a small party with friends at the Sheraton Hotel, and would I like to come? I was delighted to accept his kind offer and duly poled up at the appointed hour. It was during a week when, as it happened, the hotel was featuring nightly performances by The Hollies. Knowing their songs, and indeed having met Tony Hicks, I was intrigued and hoped to see them play. However the party I attended was independent of the concert, and so I resigned myself to a degree of disappointment - at the same time as enjoying the party and meeting Jimmy's friends.

At a given point in the evening the free flowing beer made its presence felt and I left the room to answer a call of nature. And in the gents I found myself at a handbasin standing next to - yes - the same Tony Hicks. He was of course used to being recognised, and uncomplicated about being approached when I said "it is Tony Hicks?". And then "Tony, you are unlikely to remember but 13 years ago I came to your flat in London for an audition". "13 years ago?" said he, "I can't remember last week. What are you doing now?" I muttered something about language learning and books, we shook hands and the moment passed. The meeting in 1968 had been of potential importance to me, but of course of little significance for him, and if our paths were to cross a third time I suspect he would remember neither that nor a chance encounter in the gents of the Bahrain Sheraton. Ah well, you never know. I am delighted to see that after the best part of 60 years in show business The Hollies still play with Tony prominent as one of the two original members of the band. A star.

More than a towel

1989 was the year after I had been made redundant and so was no longer an employee, and the year before I incorporated my company, and so it was the only year when I was technically, and in reality, self-employed.... My first job in this new status had been towards the end of the previous year when I was one of a team of three training ministry of education staff in Amman, Jordan over a period of ten weeks. That had gone well, so early in 1989 I was asked whether I would be free to go to Malawi on a World Bank mission. Of course I said that I was. In truth I had little idea at first what was involved but I was well-briefed by Tony Read at the Publishers Association, and then well looked after by the redoubtable economist Nwanganga Shields who led the mission. Nwanganga, now in her 90s, writes African fiction from her home in Maryland. There were 5 of us in the team, and my job was to work out the best way to invest a given sum of money in the development and production of books for teaching English, Chichewa and Mathematics at primary level. That was a quite a challenge, but Nwanganga metaphorically held my hand I was able to get on with the job. For those with longer memories of working with pre-Windows computers, in those days our reports were all generated and saved in WordPerfect and Lotus 1-2-3.

We were based part of the time in Blantyre and part of the time in Lilongwe, and I also spent a couple of nights in Zomba. I had no experience of the night life in any of those stops but it was said the bar girls carried signs saying "We do not have AIDS"; but, as one wag had it, there was no money back guarantee. I was however able to see quite a lot of the country from the seat of a Pajero, catching sight of the people in road side huts, or walking in the roads, and the jungle, the hills and the plains, and even spent a night in a camp where we were warned to beware of hippos. Part of my brief was to find out what - even whether - books were being used, and how they were distributed. The Malawians took me to a school in Blantyre where the books were apparently in good supply. I asked to see a school in the bush, well away from the city, and was duly driven across country to a village school. There was no phone locally (and no cellphones in those days) and my visit was clearly unannounced, but the headmaster (the only master there it seemed) wheeled the children out to say welcome in English (in unison) and to sing what I think was Yankee Doodle. The children were pure charm and the headmaster a gentle soul who showed me his book cupboard with some embarrassment mainly because it contained so few books, and their condition was pretty much unusable, the cupboard being mainly a home for cockroaches. Book distribution was an issue. The books were at that time mainly, at rather uncompetitive cost, produced in a private printing press belonging to a friend of the "President-for-Life" Hastings Banda, an autocrat whose title was fortunately not fully borne out.

In the capital Lilongwe, before my final sortie to Zomba, I visited inter alia the offices of the British Council and the Ministry of Education, and stayed at a comfortable hotel in the suburbs. It was there that one night, at about 11pm after I had gone to sleep, I was woken by the crashing hubbub of people getting out of the hotel where we were experiencing an earthquake. Things were falling off shelves and, although it was not my first earthquake it was frightening enough. But the special factor for me was that I was taken completely unawares and in the altogether, and could only grab a towel to put round my middle before heading for the hotel entrance. I saw immediately that I was not, shall we say, typical, and everybody else seemed to be properly dressed. Indeed there was evidently some sort of grand celebration taking place and most of the people I stood among were dressed for it, the men in black tie and the women in their finery, in stark contrast to myself doing an impression of Gandhi on a hot day. The earthquake soon relented, the building was judged to be safe and we were called back in. I was certainly one of the first to be back in my room.

I bought a paper a couple of days later to see how it had been reported, and it appeared there had been some damage to buildings, but no recorded fatalities and neither - to my relief - were there any pictures of panicked hotel guests. The paper did however make much of the fact that about 40 chickens had dropped dead - a manifestation, it was said, of mass hysteria. I hope never to be part of any such mass hysteria, neither would I wish it on any chicken present or future. But when travelling I tend to keep a pair of trousers close to the bed.

When Rebar is not enough

In 1989 the British Council came into a grant for the promotion of British ELT. That required a committee, and so the ELT Promotion Subcommittee was set to identify appropriate uses of this money, and this included ...representatives of schools, publishers and examination boards. I was directly and also indirectly a beneficiary of this committee. It was originally Nic Underhill and Geoff Cook, then of Passport Language Schools in Bromley, Kent, who put forward a proposal to the committee for a database of accredited English language courses in the UK, at that time a novel idea. The committee thought this was a good idea and so approved an allocation of several thousand pounds, and the British Council was tasked with organising this. They picked a company in Cheltenham called E2000, and reported this back to the committee. The committee was, however, less than impressed. Why had the scheme not been put out to tender? Why indeed were Nic and Geoff not invited to tender as originators of the project? The red-faced British Council immediately agreed that it should go to tender and that Nic and Geoff would be contacted. It was at this point that at their invitation I joined forces with Nic and Geoff using my "EFL Services" brand, and in time for the appointed deadline I hand delivered our tender to 10 Spring Gardens.

After due consideration - or possibly just a decent interval - the British Council announced that the company they had already contracted had won the tender. So now it was our turn to be less than impressed. We decided to press ahead with development and publication anyway, and so began the "EFL Coursefinder" database publication which was a few years later, after the failure of the British Council E2000 project, to go online and become "English in Britain". That is what I mean by being an indirect beneficiary. The public money went down the drain, but I was on a winning team on a project which had widespread support, including - after the failure of the E2000 project - substantial moral support from the British Council. The British Council had another go at marginalising our efforts, however, at the turn of the millennium with the establishment of Education UK, and by 2002 were advising schools and colleges to switch allegiance from English in Britain to Education UK, and were in part successful for a while. But while Education UK garnered the prestige of "The Prime Minister's Initiative" and lasted long enough for the Director General to leave with a knighthood and sundry British Council staff to enjoy promotions, it collapsed too, and so a rather larger sum of money turned out to have been invested in fresh air. 32 years after Nic and Geoff's original proposal, English in Britain lives on, and today once again even enjoys British Council support. Phew.

I was also, as mentioned above, a direct beneficiary of one of this committee's resolutions. There was, for political reasons which will be familiar to readers, no British Council office in Taiwan, but Taiwan was a "tiger" economy. It was, inter alia, where Alan Sugar had all his Amstrad computers manufactured, there was growing demand for English language products, and so I was asked to report on ELT opportunities there. It's a long flight to Taipei, and so when I discovered that my luggage really had been lost by KLM I was not a happy bunny. I checked into my hotel - the functionally named Hotel Rebar - and bought a change of clothes, while the hotel provided me with toothbrush, razors etc. and I was finally able to get organised. But I did not sleep well. Jetlag means that you can often get to sleep quickly because of sheer fatigue, but then wake up after an hour or so and be unable to drop off again. But on this occasion I could not in any case drop off because of the unmistakeable noises of what we might call a honeymooning couple, of otherwise admirable energy, in the room next door. After breakfast I went to the hotel desk to tell them that I wanted to change my room, and when asked why I explained that the room was noisy, and when that wasn't enough I referred to the room next door being occupied by a young man and a young woman, and the embarrassing penny dropped.

KLM produced my luggage the day after I arrived and it was a generally very interesting and enjoyable visit. One memory I have is of visiting the Merica Institute which provided TOEFL training in large rooms on three floors. In one of the rooms there was a lecturer speaking Chinese and in the other two the same lecturer on a TV monitor. So TOEFL training in Chinese. They also had a university placement service and, for those students ready to depart, a flight booking service.

The name of the hotel is still, unromantically, Rebar, although now embellished with Crowne Plaza. But don't let the name mislead you, and if you stay there it may be advisable to check with the desk about the sound proofing.

The safety of Taxis

There was a day in Tripoli when I had cause to be grateful to a taxi driver. Not a taxi I was travelling in as I do not believe that I ever got into a taxi in Libya - when we arrived ...and also when we left we were given a lift to and from the airport by colleagues and, while resident in the country, I had a car which took me to work, to Leptis Magna, Sabratha, Cyrene and the Jabal Akhdar, and Ghadames. This was a taxi that just happened to be driving behind me as we headed down the Khoms road towards Tripoli centre. Really quite close to the centre there was, anomalously, a stretch of open ground where a man was tending his sheep. I was driving so barely aware of what happened but out of the corner of my eye I saw the sheep nearby and one in particular heading for the car. And I hit it. I missed it with the front of the car but the confused sheep ran into us and the nearside rear wheel hit a leg and the poor sheep lay in distress in the road behind me and in front of the taxi. At this point the understandably upset - and irate - shepherd appeared brandishing a sizable knife and I got out of the car to talk to him, and hopefully discourage him from using it on me. I tried to protest my innocence but he was clearly very upset - at which point the taxi driver got out and told the shepherd "huwa salim" - literally "he is sound" and thus established my innocence. And so the knife was used to cut the throat of the sheep, its blood poured copiously on to the roadside, and I was able to leave. That was in 1973.

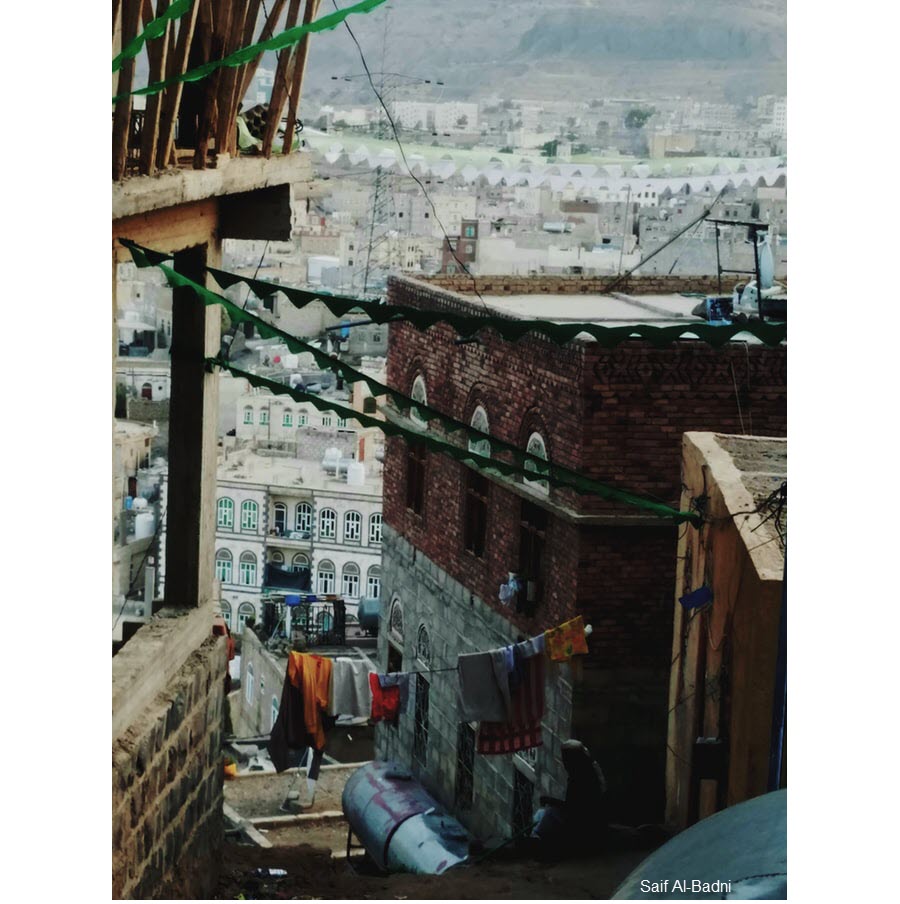

It was some years later - in 1989 in fact - that I had occasion to thank a taxi driver for more than just the ride. I was tasked by the Overseas Development Agency to provide a progress report on a project called "English for Yemen" which was being managed by the British Council. At that time it meant flying to Frankfurt and then joining a Lufthansa flight to Sana'a. As luck would have it I was upgraded to first class, and enjoyed a comfortable flight. At Sana'a either because of special security measures, or because of chronic inefficiency or bloody-mindedness - or perhaps a combination of all three - it took two hours for luggage from the flight to appear, and with the time difference it was getting on for two o'clock in the morning before I finally got into a taxi to take me to my hotel which, as it turned out, was a few miles outside Sana'a. On the way we were stopped by two armed soldiers, one of whom pointed his rifle at me through the car window and asked who I was. The driver explained that my credentials were in order, he was taking me from the airport to the hotel and there was nothing to investigate. I was asked for my passport which they looked at cursorily, merely establishing that I had such a thing, and that was that. It was to my knowledge the only time I have had a gun pointed at me and I can say that I never thought for a second that it would be used, and - unlike the moment with the Tripoli shepherd - experienced no fear.

The English for Yemen project was, to be frank, in very poor shape, and the Yemeni authorities were distinctly underwhelmed by British book development expertise. It was taxpayers' money that was being used for the project, and for my report, and the Yemeni ministry contact expressed gratitude for that, but it went no further. The principal matter at issue was the poor quality of design and production, the illustrations, the look and feel of the books. There were two British authors in situ but the team factor was not working. The Yemenis were also unhappy with the content, and I was shown a page with a photo of a Yemeni with the caption "Silly Ali has forgotten to put oil in his tractor" - which was evidently deemed an unsatisfactory model for secondary school children to sign up to, and judged to be something of an insult from people who were guests in their country. And it turned out that the Yemenis were being encouraged to adopt the Arab World series developed by the Beirut company Oxford University Press (OUP ELTA). Indeed, I was told, Kuwait had offered to meet the full cost of supplying the books to Yemeni secondary schools.

My report to the ODA cannot have gladdened them. I said that the project looked to be beached already, but might perhaps be rescued by a high level visit from the British Council. In the event the Yemenis pulled the plug first and another dollop of taxpayers' money went down the pan.

But it was not all painful and negative. The mountainous backdrop and the architecture of Sana'a are unique and not to be missed and the people - when not drugged to the eyeballs with Qat - were at all times kind and welcoming. Except once.

Neighbours

If you are lucky enough to have been to Ireland and to have seen the country and mixed with the people, you will know that Ireland and its people are very like Britain and its people, only different. Over the years ...I have been a dozen or so times, and each time I am reminded of that difference. The English have no rival for the least loved nation in the British Isles, and are themselves generally ambivalent about their nationhood, typically referring to themselves as "British" in a way that the Scots or Welsh do either much less or never. Remember the Flanders and Swan song with the chorus "The English, the English, the English are best, so up with the English and down with the rest"? It was an exceptional indulgence, and as they said in their introduction, the rationale for it was because just about the only national song about England was called "Jerusalem". The Scots and the Welsh have a strong sense of national identity which stretches - to breaking point for many - their support for the union. And there's Ireland. In Dublin, an Irishman who had invited me for coffee and who then, rather stylishly, without further question or comment served me a pint of Guinness, told me with a smile that there were two kinds of people in the world, the Irish and those would like to be. What other nation would dare to say the same (and why did I suspect he might be right)?

Irish jokes we have all heard, but the best Irish jokes are told by the Irish - who can forget the rich vein that was tapped over many years by Dave Allen? Not all of his were "Irish" jokes of course, but even if the subject matter wasn't exclusively Irish there was typically an Irish flavour or touch. It's the Irish who have the best jokes about Ireland, and in fact it's also the Irish who have the best true stories of the "you can't get there from here" genre. But I have a couple as well.

The first isn't mine. My brother - a ceramic artist with a network of colleagues in many places - once stopped at a little bar in a village in county Cork where he was looking for a friend's house, and asked for the street by name, and the barman immediately offered to come outside with him and show him. "You go along here about quarter of a mile" he said pointing further down the road, "and then you turn..." he hesitated. "Left?" my brother suggested. "That's the one" said the barman.

My first trip to Ireland was to an IATEFL conference held in Dublin in 1990, where for the first time I met Tom Doyle and Declan Millar who were the Irish IATEFL pillars at the time and who I would have the pleasure of meeting at conferences and events many times over the following 25-30 years. For the duration of the conference, which was held on the splendid Trinity College campus, I stayed at a city centre hotel which was friendly and comfortable, a hotel like many others. In those days it was quite common to order a morning call from the front desk rather than from an automated system and to be sure that I didn't oversleep on the first day I ordered an alarm call for 7.30 which was noted by the receptionist. The following day I went downstairs for an excellent "Full Irish" buffet breakfast of the kind where the staff put food on your plate before handing it to you fully laden to be carried to your table - "Would you like mushrooms with that?" "Yes, please" "I like 'em too" - and afterwards went back to my room to collect my coat and papers. Just as I was leaving the room the phone rang, and I walked over to the bed to pick up the receiver. "Was it you ordered the call for half past seven this morning?" "Yes it was", I said. "Well, thank heavens for that. It's ten to nine".

An Inspector Calls

I got plenty of British Council inspection work from the end of 1988 onwards and that suited me very well because in the autumn of that year I was made redundant by ...the publishing company I worked for in London (Unwin Hyman - they sold their ELT interests to Nelson) and I became self-employed. My co-inspectors were apparently content for me to be the reporting inspector for each inspection, and it was interesting work which I was happy to undertake. In 1990 I was asked to be one of two inspectors to pioneer the so-called "spot-check" inspections. The schools had evidently agreed to this element of quality assurance, although an unannounced visit by an inspector can never have been exactly welcome. I did a fair number of these. Although the official line was that the schools had been chosen at random, I was pretty sure that I had mainly been sent in to investigate operators whose standards were in question. This is the story of one such inspection.

The school was in Devon, too much of trek from East Anglia for a day return and so I spent the previous night close by at a B&B. It meant that I was able to turn up at the school punctually at 9 a.m. which meant in turn a wait of over one hour before the principal - who we shall call Mr Harty - appeared. When he did, he asked - quite reasonably - who I was and what I was doing. When I advised that I was doing a spot-check for the British Council he clearly had no idea what I was talking about. Rather than telephone the Accreditation Unit as I suggested he asked me to explain what was what and decided with some reluctance to believe my story (having also advised me that he never read anything sent to him by the British Council).

At my request he then gave me a tour of the building. It was a substantial former manor house and quite suitable in terms of size and scope to be a language school, but it was run down and in need of decoration, carpeting, fittings. Perhaps sensing my assessment, the tour included a moment when he threw open a door with a flourish and announced that this (in truth another indifferent storage room) had once been the bedroom of the man who broke the bank at Monte Carlo. I decided not to pursue that - I had heard the song but neither the song nor his unlikely story could be said to be pertinent to the occasion and we moved on. In the staff room Mr Harty said "I know, you're looking at that chair". Thanks to this remark I now noticed that one of the chairs in the staffroom had three legs and was tipped at an angle at which nobody could possibly wish to sit. I looked at him questioningly. "That chair", he said, "just goes on coming back because the teachers love it. I've thrown it out and put it on the dump, but they just rescued it, so there it is." Just outside the staff room there was a photocopier, with a sign above it for the attention of the staff which read "Staff photocopy copyright material at their own risk". "You see" he said with a wink "I don't tell them they can't do it, only that it's their problem if they are caught".

More serious - from the point of view of accreditation at least - was the absence of a director of studies and in consequence the apparent absence of any educational management. I asked Mr Harty about this who told me that the reason for no DOS was that his DOS was ill. "Very ill", he said, "in fact he almost popped his clogs". He didn't know when or even whether he would return. I asked (as we had to in those days) for sight of his VAT returns, but nothing was produced. And so the day wore on while I talked to students and staff and visited classes, and I asked Mr Harty for a short meeting before I left. I told him of my findings and of my concerns and said that these would be reported to the British Council. And finally I asked him if there was anything he would like to say to me before I left. "Yes", he said. "Don't come back".

A Sparrow and a Mighty Cow

I knew very little about Jamaica before I went there. Before anybody jumps on me I will be the first to say that two weeks there does not make me any sort of expert, but it was a big advance from my pre-Jamaica position. For example, ...I had from school learned and played the song "Jamaica Farewell" from listening to Harry Belafonte's beautiful recording of it, and knew - or at least I parroted - the words to all the verses. But I am ashamed to say that I not only did not know, but did not even try to find out what was being said in the line "ackee rice saltfish are nice". I just liked the sound of the line and that was enough. But once in Jamaica I discovered for myself the meaning of ackee and saltfish, callaloo, jerk chicken, the taste of local herbs and spices, of Red Stripe and the sound of the Reggae beat coming from sundry loud speakers and the plentiful "ghetto-blasters". But it was the friendliness and the hospitality of the people who I was there to train, and the way they looked after me that was so heart-warming and which made the visit such a pleasure.

My fellow-trainer Susie Home stayed with friends while I was put up at the Liguanea Club in New Kingston. The club had an excellent pool and a pleasant restaurant, plus many other facilities which I had no time to use, and it lies across the street from the Pegasus Hotel where I could go for any essentials. Susie was giving a course in design and production while my brief was concerned with editorial management from commissioning through to editorial production, and our trainees were all employees of Heinemann Caribbean. The trainees were keen and very good company, and I am in contact still today, 31 years later, with one of their number - now an old friend. It was outside the training seminars that they went beyond the call, and I was taken to places that I would never have considered going to alone, and would not have enjoyed on my own anyway. I was looked after and in effect protected by my protegés - in bars, restaurants and museums, and on the street.

There are two incidents that I recall with particular pleasure. At school I had a friend and contemporary who lived in Trinidad, and it was he who introduced me to calypso. The songs he had on record were performed by, among others, Nina and Frederik, Danes; they sang nicely but one wonders whether today they could get away with a song called "When woman say no she mean yes". It was however the infectious beat and the backing (and the cheek) of the songs by The Mighty Sparrow that got us moving. And, on this occasion many years later, The Mighty Sparrow was on tour in Jamaica and my blessed trainees took me to hear him. It's not as if a packed crowd of Jamaicans need to be cheered up - it was sheer animation, sheer fun from start to finish. Meanwhile even today The Mighty Sparrow is still going strong in his mid-80s. Enjoy, for example, Jean and Dinah, but as with the Nina and Frederik song don't listen too carefully to the words if political correctness is your thing.

The other incident was a weekend picnic. A bunch of us headed for the hills, driving past apparently innumerable churches with names permed from Almighty, God, Heaven, Saviour, Salvation, Jesus, Christ, Redeemer, Redemption, Spirit and so on - there might have been one called, say, the Church of Universal Salvation through Christ the Redeemer - but then I might have made that up. It was a very hot day and we stopped and unpacked the cars by a stream that flowed through a meadow where cows were grazing. We ate and drank at first by the stream, and then in the stream - we sat in the water eating and drinking and talking and laughing. The good company and the Red Stripe made me feel particularly benign, but the feeling was evidently not shared by the cow that I chose to pat as we left and who delivered a very sharp kick. Not enough to spoil a great day.

Remembering it now in Covid-19 oppressed Britain, it seems extraordinary that I was paid for what I was doing. Such enjoyable work with such great people in such an exciting place - it seems like a dream. But for the cow.

Meads

My involvement with the language school administration software that would be branded and known as Stream-Line can be traced to a delayed train and two strangers ...standing side by side at the station in Tunbridge Wells. The delay licensed a grumble, and they started talking to each other. One of them was Paul Mason who ran a language school in Tunbridge Wells called Cicero Languages, and the other was Jack Schuldenfrei, the manager of the British Council English Teaching centre in Tel Aviv, and it didn't take long for them to find common ground. Jack told Paul that his son Michael was developing software for language school management and Paul who I knew because his school was an early subscriber to our English language course database - his school was actually record number 1 - passed this news and, with their blessing, the Schuldenfrei contact details on to me. I met Michael soon afterwards. He had commitments in Israel that lay ahead, and we readily agreed that my role was to be the effective publisher and global contact for the sale, development and support of the software.

At that time people generally, and language school managers in particular, knew little about software - some schools had no computers of any kind, some had a dedicated word processor, but it was mainly virgin territory. However, just as we came out with Stream-Line, a competitor emerged in the shape of Infospeed. Their software was radically different from ours; I will pass over what the differences were but it did mean that we talked to interested schools with quite different propositions. I recall nevertheless that an early sale we made was to a school where the owner said that he knew there was an alternative to what I was offering, but he probably would not understand the difference so he would place the order with me.

It was a very different age. To demonstrate the software it was almost always necessary to do it in person using a computer on which the software was already installed. Thus I would travel from Cambridgeshire to Paignton, or Manchester or Edinburgh, where I would unload a heavy computer, keyboard and CRT monitor in order to show a school what it was all about. And indeed I travelled much further. By now armed with an expensive and very clunky laptop, I went, for example, for a one night trip to Frankfurt to visit a school (at their expense), and for one night to Malaga, and failed to make the sale on both occasions. But we also had some brilliant success as when for example I was summoned by David Jones, the CEO of EF International schools, to London, where we agreed on a deal to supply all EF International Schools worldwide. It was adopted in by schools in Canada, the USA, New Zealand, Australia, Mexico, Paraguay and Ecuador, in Namibia, Cambodia and Senegal as well as more obviously in Europe, the UK and Ireland. It was an adventure that took me to Dublin and Galway, to Norfolk Virginia and Chicago, to Vancouver and San Francisco, to Brisbane and Sydney. And I was meanwhile supporting users everywhere by fax. It was DOS software and the last sale we made was early 1997.

This story is about one of those occasions when I failed to make a sale. I was in Eastbourne visiting a school, now closed, called Meads School of English for Foreign Students. The school was owned and still largely run by Major Douglas MacRae-Brown who would have been in his 70s at the time. He was a nice man of a particular British ex-army type, a man of whom it might have been said - kindly - that he was a "buffer". At a given moment he enquired about accommodation management, remarking that it was important. I told him I knew of this having run a school in Cambridge, and told him how in the summer we would take on an extra assistant accommodation manager and that sometimes that was not enough and so I would also, as principal, take on host families. "So did I", boomed the major, "on my horse. I would ride around the streets of Eastbourne and from that height I could usually see if their front room was presentable, and if it was I would ask them if they would like to host a foreign student".

The practice of recruiting host families by horse had, for a number of reasons, ceased some years before that visit to Eastbourne, and indeed before any language school considered using a computer for any purpose. Douglas MacRae-Brown is remembered for being inter alia the man who tended, annually, the grave of the poet Rupert Brooke on the Isle of Skyros - that corner of a foreign field that is forever England.

Two Nights in Perth

Towards the end of 1991 I travelled on business to Australia, with stops in Brisbane, Sydney and Perth, where I spent my last two nights. The flight from Sydney to Perth ...is an education in itself - a three hour time difference and a flight time akin to travelling from London to the Middle East. When I got there I was looking forward to a cool hotel room and putting my feet up, but it didn't quite work out that way. The main purpose of my visit was to drop in on a client school - St Mark's International College - and they booked me into a nearby Motel. It was December and my hotel room was stifling, airless and hot, and I decided to go to the bar as quickly as possible. I walked in, stood at the bar and was served a beer. Well, the barman took the cap off the bottle.

I took my first sip out of the bottle and looked around me. The fellow next to me had clearly had a skinful and needed both hands to keep him upright while he gripped the bar. But on seeing me and catching my eye he chanced an arm and thrust it out for a handshake. "Larry" he said. "David" I replied. "Pleased to meet you, Craig" he said. Yes, that's right. I'm not saying I pronounced my name perfectly, but I had the feeling that the linguistic tangle had taken place somewhere else and so decided not to correct him. He evidently didn't object to Poms, although his dislike of Kiwis was marked - one truth I was invited to take from our encounter was never to trust an effing Kiwi. I asked him what he did and he told me he was a trade union official, and I encouraged him to talk about that. Conversations with strangers sometimes take their own turn, and he began to talk about how he liaised between workers and management in the large company where he was employed, and that included some unlikely and, frankly, shocking stories of how he accepted payments from the management to keep the union members as compliant as possible. He said goodnight and somehow staggered out of the bar.

I spent most of the following day at St Mark's configuring the software for the reports and documents they needed, and visiting a couple of schools. The motel had no restaurant, and so after a quick shower I went to a nearby Vietnamese restaurant for dinner. The restaurant was empty but for a young couple, and I seated myself a suitable distance away from them, but it was only a few minutes before they engaged me in conversation and shortly afterwards joined me at my table - one of many encounters I had where the Aussies showed their easy, open friendliness and hospitality. Having enjoyed my meal more than I had expected to, I said goodnight and headed back to the hotel bar. There at the bar was Larry once again, and clearly with a lower centre of gravity and in better shape than he had been the previous evening. "Hello Craig" he greeted me, "how are you?". "Fine thank you Larry", I said, "and how are you?". He was, I think, quite impressed that I had remembered his name, but not nearly as impressed as I was that he had remembered mine.

A Fortnight in Senegal

The devaluation of the CFA about two weeks before I went to Dakar in February 1994 was very convenient for me, but not so much for the people of Senegal who very quickly experienced a sharp increase in the ...price of just about everything. I spent two weeks there under an Overseas Development Agency programme, and my job was to oversee the installation and training of staff at the British Senegalese Institute, where our software product Stream-Line had been selected as the right product for the job. Stream-Line was at that time used in multiple schools and institutes in main international language markets - the UK, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, the USA, Canada - but also, more exotically, was used by local institutes in Ecuador, Paraguay, Cambodia, Namibia - so the choice of software, for the purpose of student registration, class assignment, billing etc., was entirely appropriate. What became apparent during my visit there was that while the administrative staff were keen, responsive and generally positive about the programme, there was no interest at all in cutting back on the manpower needed for the administration of the institute. And, indeed, why should there be? They had good jobs, and these were generally scarce.